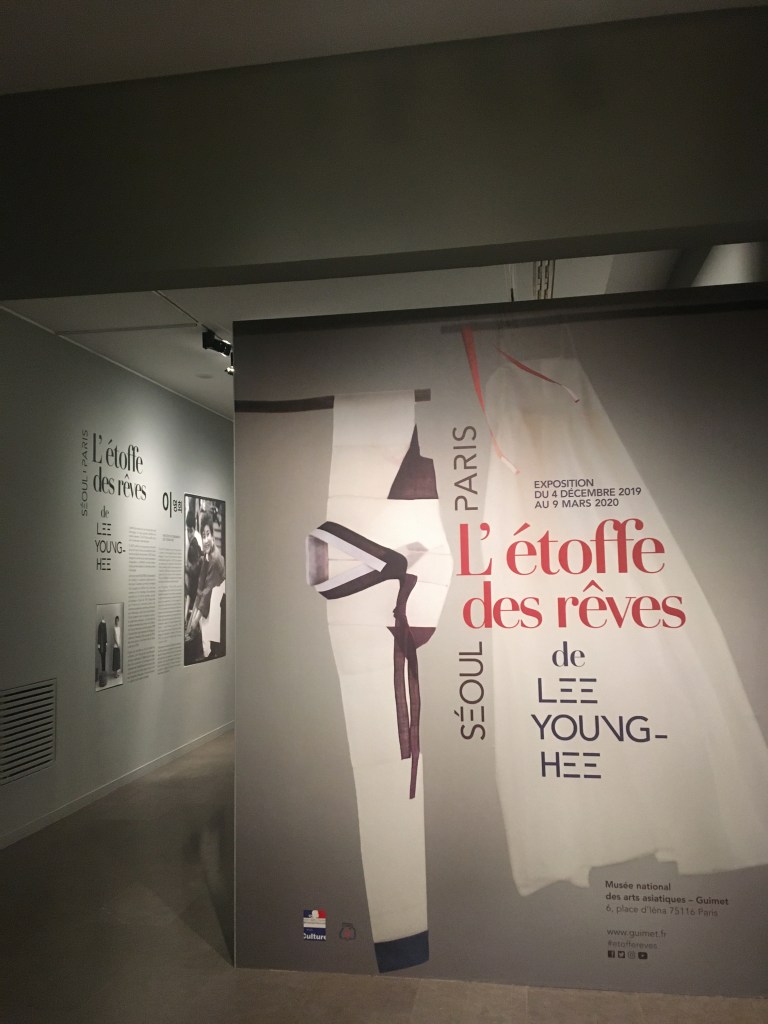

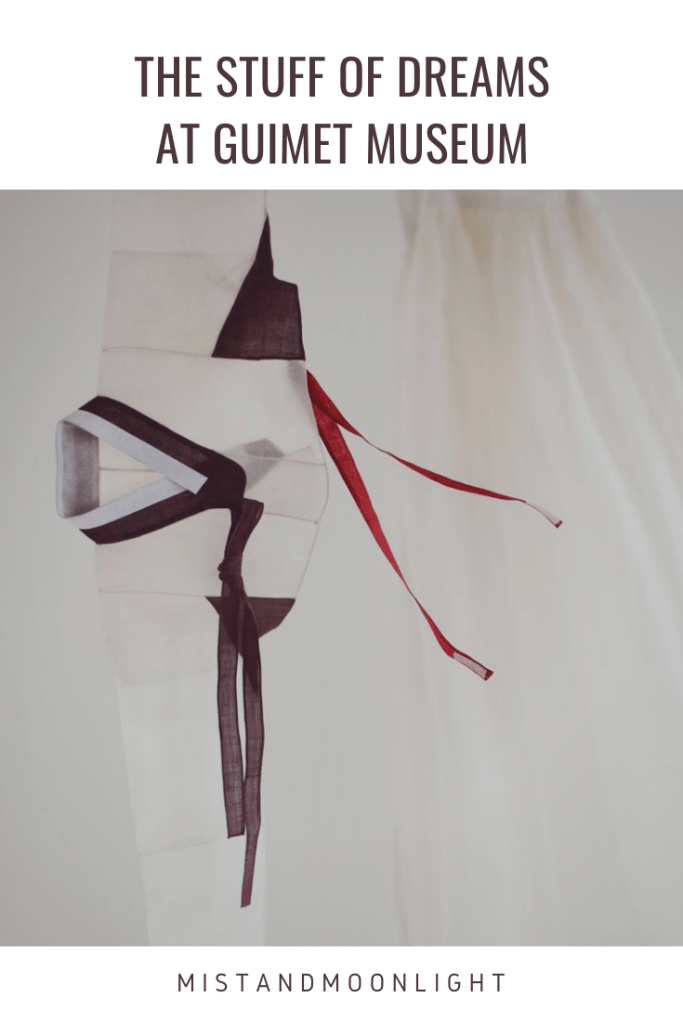

At the beginning of March I went to see the exhibition L’Étoffe des Rêves (The Stuff Of Dreams) at the Guimet Museum in Paris, highlighting the work of Lee Young Hee – 이영희, one of the greatest Korean fashion designer.

I almost did not get the chance to see this exceptional exhibition that everyone had told me about. It was visible from 4th December 2019 to 9th March 2020. Returning from my working holiday visa from South Korea on 2nd o fMarch 2020, I only had one week to go to Paris and enjoy it. It’s not every day you get the chance, whether in Korea or France, to explore the history of Korean costume and its influence on fashion.

Passionate about Korean costume history, I found it difficult to look for informations about it or museums who are only dedicated to it. It’s a shame, but it makes the informations hunt even more exciting.

I had to go see this exhibition and I was more than happy. I discovered a new textile designer, a new way of seeing and designing Korean textile art and new knowledge on Korean costume, The Hanbok – 한복.

L’Étoffe des Rêves (The Stuff Of Dreams) pays homage to Lee Young Hee – 이영희 (24th February 1936 – 17th May 2018), Korean fashion designer who has promulgated outside of her country the art of Hanbok – 한복 and who received an international consecration in the 90s.

In 2019, his daughter, Lee Jung Woo – 이정우 made an exceptional donation of nearly 1,300 pieces to Guimet Museum in memory of the special bond between the artist and Paris. The Museum now has the largest collection of Korean textiles abroad.

PIONEER OF THE KOREAN COSTUME HISTORY

Lee Young Hee’s passion for traditional costume of her country was passed on to her by her mother, who taught her the meticulous and delicate art of dyeing and assembly. After the opening of his shop called Korean Dress by Lee Young Hee in Seoul in 1976, her success was quickly established thanks to her choice of natural materials (silk, ramie), the quality of the finishing and the refinement of her creations. Her clientele included many personalities like the first ladies or Korean stars.

Lee Young Hee – 이영희 workshop

Driven by her love for the history of Hanbok – 한복, she began researching its history.

She also worked from the 1980s to promote Korean fashion internationally. It was from 1993 that her link with France began with her Haute Couture fashion shows.

Lee Young Hee – 이영희 is an example of Korean modernity and the ability of Koreans to adapt changing while retaining their traditional values and protecting their skills.

“The handbook is my whole life. I think I was born because the handbook exists. “

Lee Young Hee – 이영희

THE ACCESSORIES

The hanbok, feminine as well as masculine, is completed by various useful accessories but also indicators of social status.

Passementerie Ornaments, Norigae – 노리개

The Norigae – 노리개 are accessories that Korean women hang on the belt of their skirt or on the ribbon of their jacket called Jeogori – 저고리. They consist of knotted cords and tassels of passementerie, to which are added one to three accessories or ornaments, incense box, needle case, keys, dagger, charms including a toothpick and an ear curette, tiger claws , lucky figurines and bells to ward off bad luck.

Norigae – 노리개 in embroidered and applied silk fabrics, silver, enamel, jade, amber, coral, horsehair. Binyeo – 비녀 hair pins and ornaments in partially gilded silver, enamel, jade, amber, coral, pearl, bamboo, ox horn. Wood, bamboo, metal, paper and embroidered silk fans.

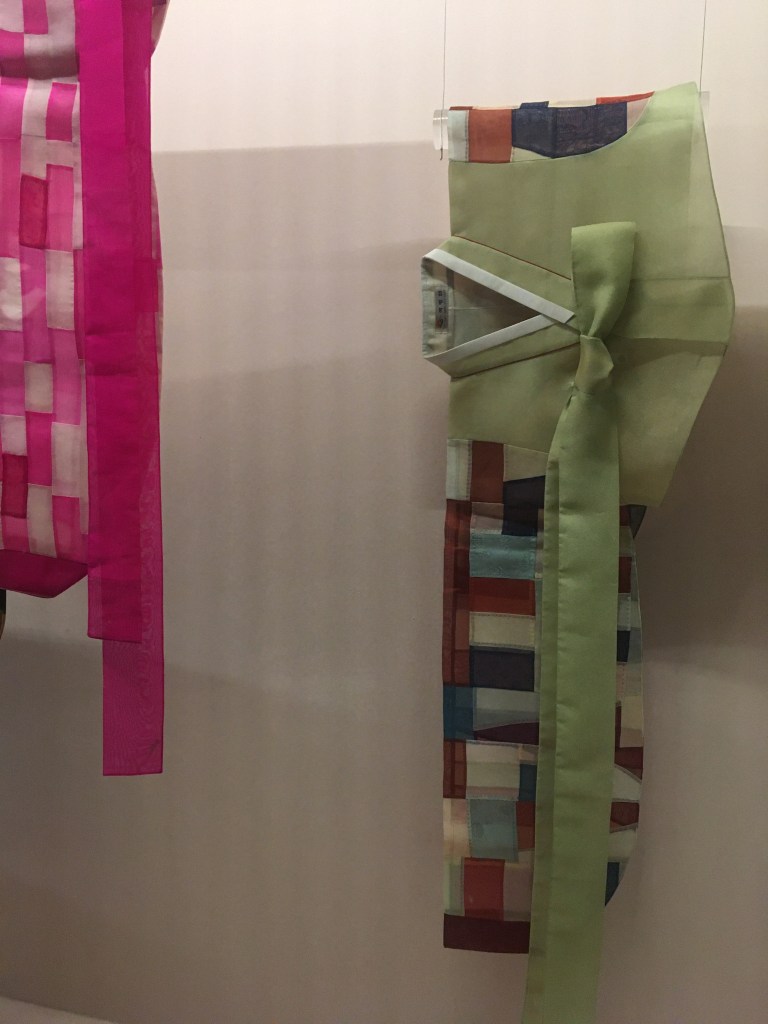

Bojagi/Pojagi – 보자기

Literally “clothes for things”, these are squares or rectangles of fabric traditionally used in Korea to cover, wrap and transport all kinds of objects, including food.

Often considered as good luck charms, they are used for ritual or decorative purposes by all classes of society. Their clothing, which uses different skills in needlework, is the work of women in their homes.

Embroidered bojagi called Subo – 수보

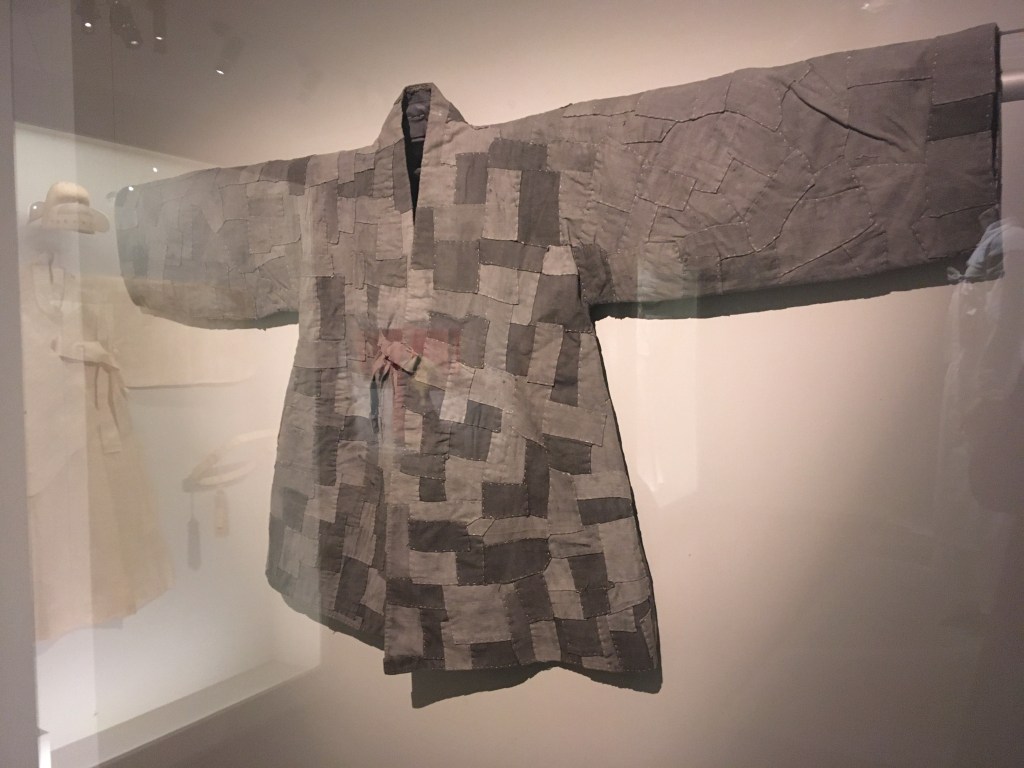

Patchwork is the first technique used for making bojagi. Scraps of fabric were generally used for making clothes. They were classified by material and by color to make the choice of creations easier. Two types of patchwork could then be made. One with regular geometric shapes made of medium-sized pieces and the other like a mosaic, with very small pieces of fabrics with irregular shapes.

Shape silk gauze Hangra – 항라 in patchwork

Women’s Headdress Keunmeoli – 큰머리

The Keunmoeli – 큰머리 headdress, also called Tteogujimeoli – 떠구지 머리 was one of the headdresses worn at court and reserved for special ceremonies for the queens, royal concubines, royal consorts and high-ranking ladies in court.

The large braided hair rings of the Keuneoli – 큰머리 hairstyle were once made of human hair. Since the ban on this use at the end of the 18th century, a carved wooden element Ddeoguji – 떠구지 was combined with a wig call Gache – 가체 / Dari – 다리 forming a thick crown resting on a cushion at the top of the forehead and enhanced with pins Ddeoljam – 떨잠.

Replica by Lee Young Hee for the wig and the cushion. Wood and Polyester.

Women’s Headdress Jokduri – 족두리

The headdress Jokduri – 족두리 also called Jokgwan – 족관 was used for certain special ceremonies such as marriage. The headdress Hwagwan – 화관 is the more elaborate version with more ornaments and therefore more expensive.

Jokduri – 족두리 in silk on cardboard frame, metal wire, enameled metal ornaments, stones and faux pearls

Masculine Hats Gat – 갓

Hat occupies an essential place in the male wardrobe in Korea. It was intended to protect but also to highlight the Sangtu – 상투, a bun bringing together on the top of the head long hair that the Confucian tradition forbade to cut. Its shape, dimensions and color indicated the rank of its wearer.

Hat Gat – 갓 : Heukrip – 흑립, black lacquered horsehair mesh on bamboo frame, jade. Cholib – 초립, Ordinary hat in woven straw on bamboo frame. Jeonlib – 전립, Military hat worn by an official in horsehair, metal, jade, silk trimmings, feather.

HANBOK – 한복

The hanbok, which means “Korean clothing”, consists of a jacket Jeogori – 저고리 associated with a skirt Chima – 치마 for women or pants Baji – 바지 for men. This set is completed, depending on the wearer’s rank, the season, or the occasion, by various top dresses, vests, jackets, or coats, accompanied by accessories: headdresses and hats, hairpins, fans, belts, shoes, socks and underwear.

Women’s Hanbok: Short jacket Jeogori – 저고리 and skirt Chima – 치마

What can be learned from the history of hanbok is that it has remained almost unchanged over the centuries. Its origin dates from the time of the Three Kingdoms – 삼국 시대 (57 BC – 668 AD), at that time the garment was also composed of two parts. Since the Goryeo – 고려 (918-1392) and Joseon – 초선 (1392-1910) eras, the jacket Jeogori – 저고리 has been closed with a ribbon Goreum – 고름 attached to the extension of the neck band and tied on the right side.

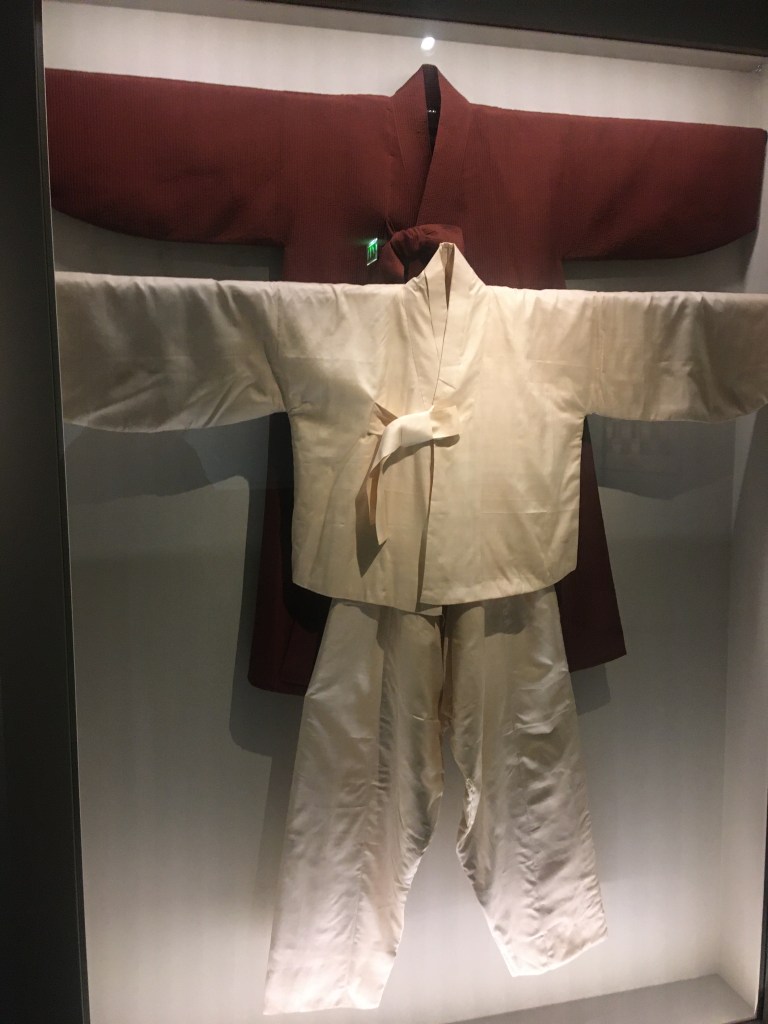

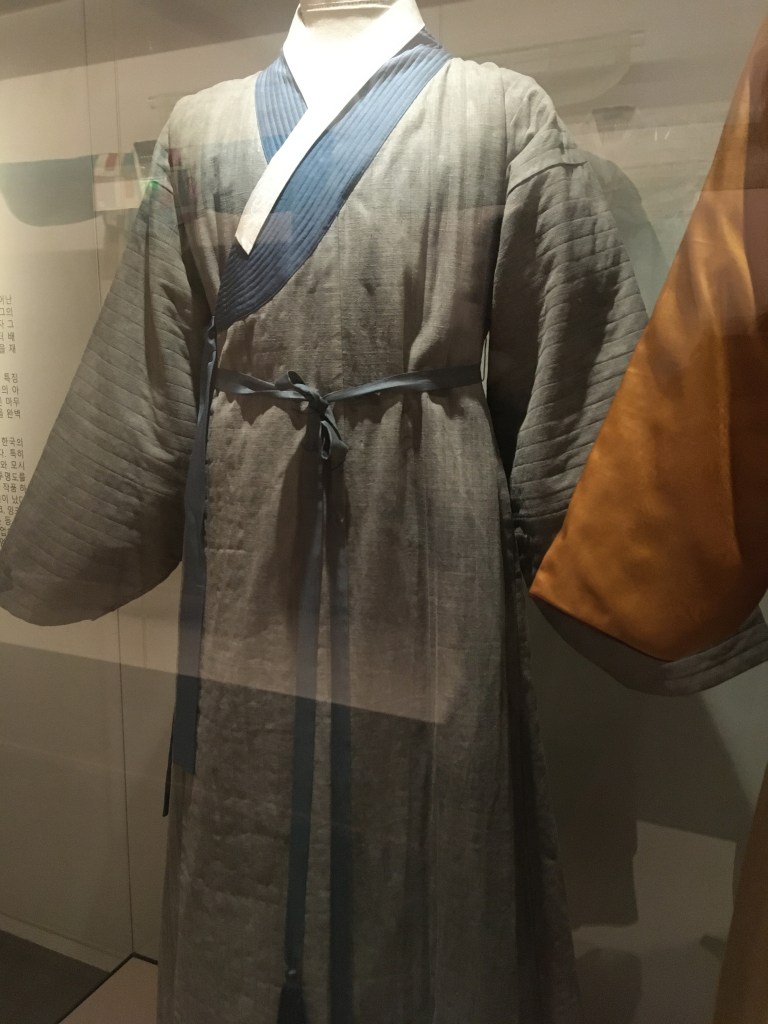

Men’s Hanbok: Coat Durumagi – 두루마기, jacket Jeogori – 저고리 and pants Baji – 바지.

The male outfit was to be completed by one or more outer garments: vest or coat. A top dress Po – 포 with wide sleeves prevailed for a long time in the aristocracy but was replaced in the 19th century by a coat with fitted sleeves in the Mongol style called Durumagi – 두루마기.

Women’s Hanbok: Short jacket Jeogori – 저고리 and vest.

With westernization, in the second half of the 20th century, the hanbok gradually disappeared. Today, it is only worn for certain occasions such as weddings, first anniversary ceremonies Doljanchi – 돌잔치 or Lunar New Year celebrations Seollal – 설날.

With the help of his teacher Seok Ju-Seon – 석주선, scholar, ethnologist, collector and great specialist in Korean clothing, Lee Young Hee is dedicated to resuscitating the clothes of the past, giving birth to reconstructions of old clothes now rare, altered or even missing. We can find the ceremonial clothes of the royal couple and the ladies of the court, the outfits of scholars, civil servants and soldiers, the costumes of dancers, musicians and courtesans, as well as the clothes worn daily by the common people, without forgetting the children’s clothes that she particularly liked. To do this, it relies on an in-depth study of preserved clothing and old paintings. Her “re-creation” work pursues a double objective of beauty and historical fidelity in the choice of materials, techniques, colors and patterns.

These reconstructions occupy an essential place in her work. In the 1980s, she shown them on catwalk, usually in the first part, before her contemporary creations.

Ceremony jacket Dangui – 당의, shaped silk gauze, shaded with gold, embroidered silk taffeta and gold thread.

Dangui – 당의 jacket was worn by women of the aristocracy for ordinary court occasions. Of medium length, its front panels are hollowed out in an arc and its lower hem is rounded forming a “crescent moon”. Like all other court clothing, it has an embroidered decoration embossed with gold.

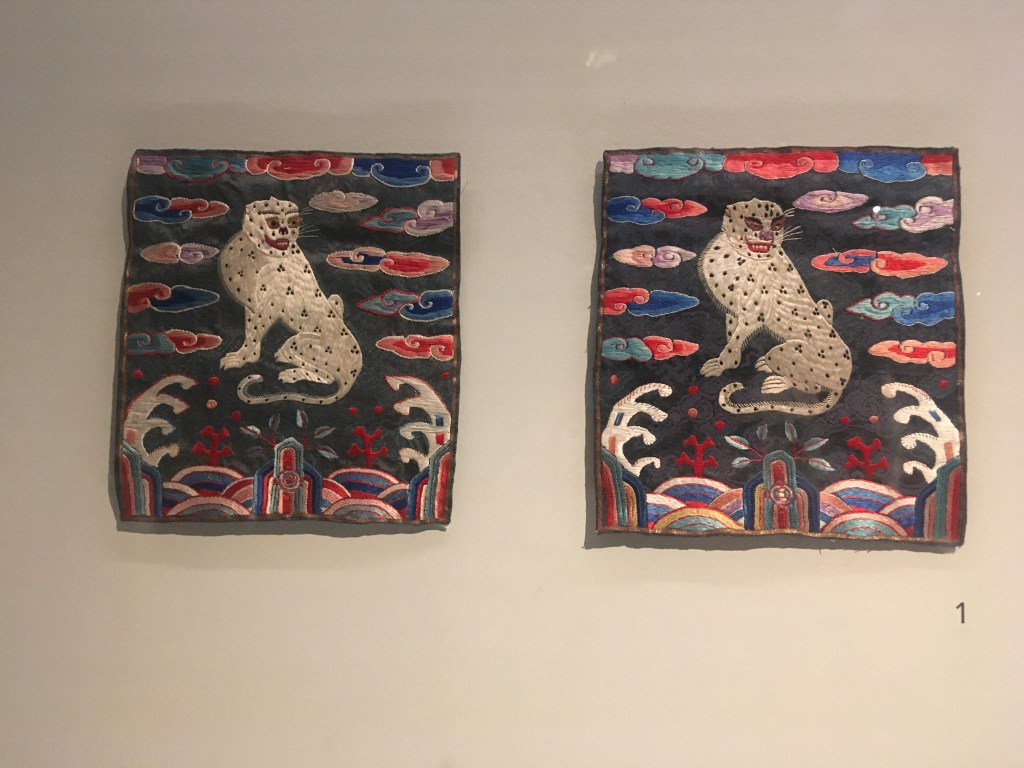

Pair of civil servant badges, Embroidered silk satin

The badge Hyungbae – 흉배 embroidered on the dress of officials of the Joseon dynasty from the 15th century onwards are borrowed from the official clothing of Ming China (1398-1644). One could represent there a crane or a hybrid being half-tiger half-leopard called Hopyo – 호표 and was used to recognize the rank of the officials.

Uniform of civil servant Gwanbok – 관복. Shaped silk gauze jackets and vest. Silk gauze coat, embroidery and gold thread. Taffeta pants. Headdress in cardboard and bamboo frame covered with shaped silk gauze. Leather shoe. Wooden screen and silk gauze.

The Gwanbok – 관복, the official attire of civil and military officials includes a Po – 포 dress with a round neckline called Dallyeong – 단령 embellished with square rank badges Hyungbae – 흉배 on the chest and back. It is completed with a Samo – 사모 winged headdress, a belt decorated with jade or rhino horn plates and leather shoes. When they went out and did not want to be recognized, they hid their faces behind a screen of blue silk gauze called Saseon – 사선.

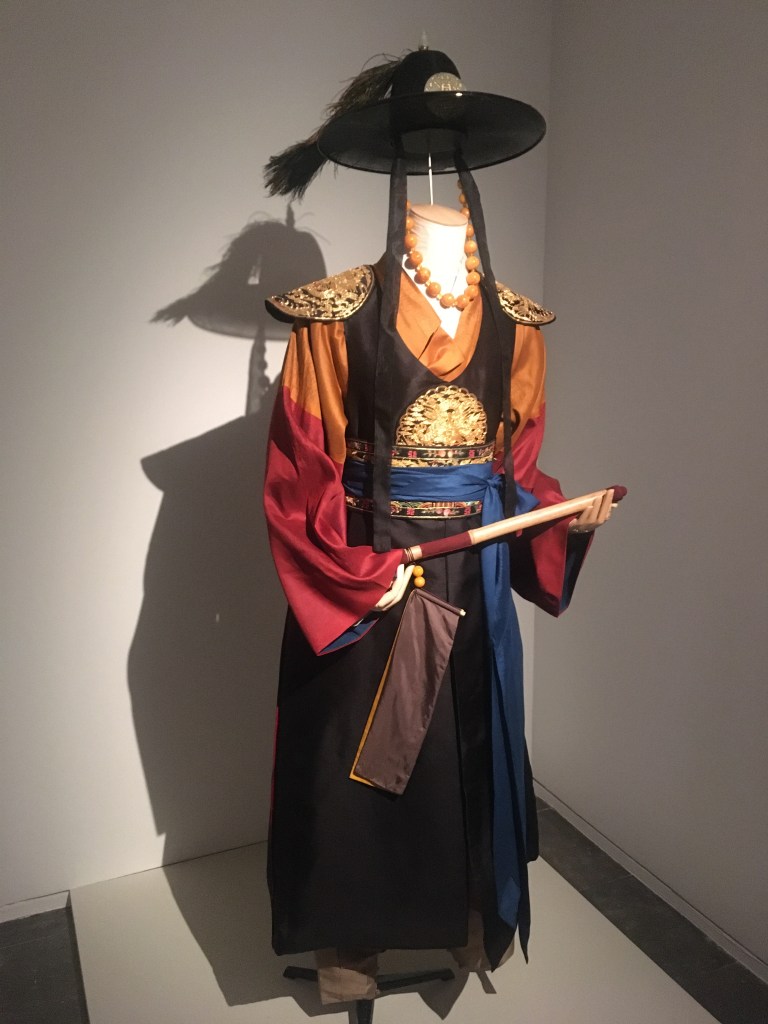

Uniform of military official Gugunbok – 구군복. Garment and belt in shaped silk gauze, damask, embroidery, gold thread. Leather shoe. Lacquered horsehair hat on bamboo frame, jades, amber beads and peacock feathers. Bamboo and silk stick.

An official’s military uniform consists of a long sleeveless vest Jeonbok – 전복, a belt Jeondae – 전대 and a coat Dongdali – 동 다리. There is also a underwear jacket Jeogori – 저고리 and a pants Baji – 바지.

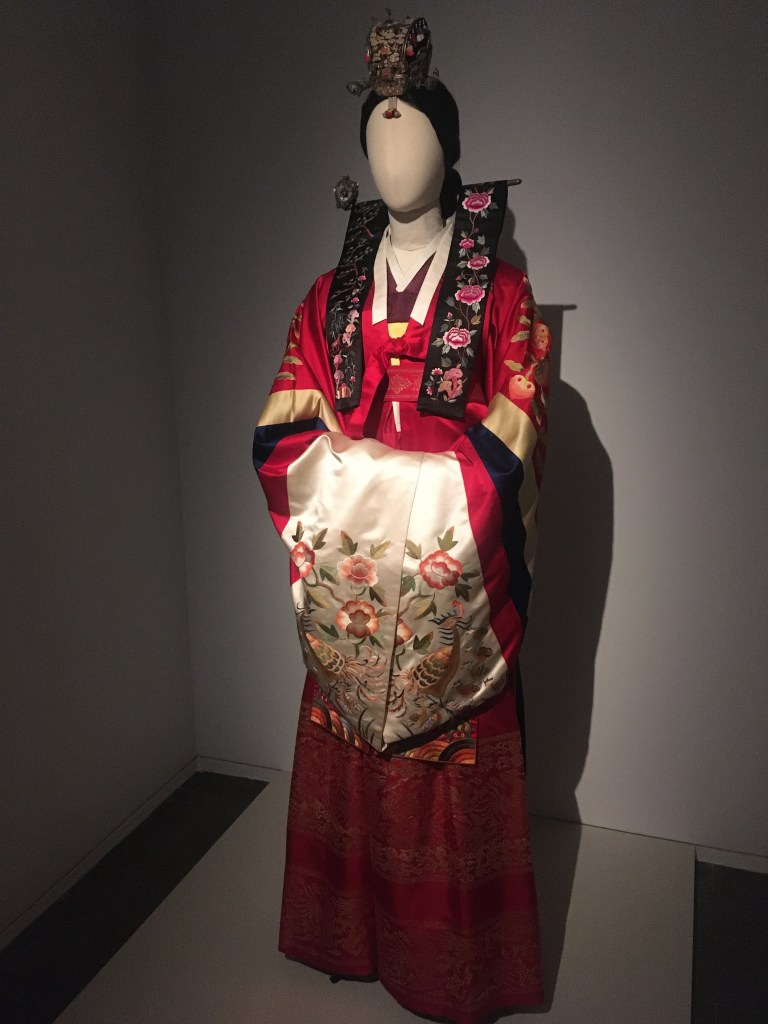

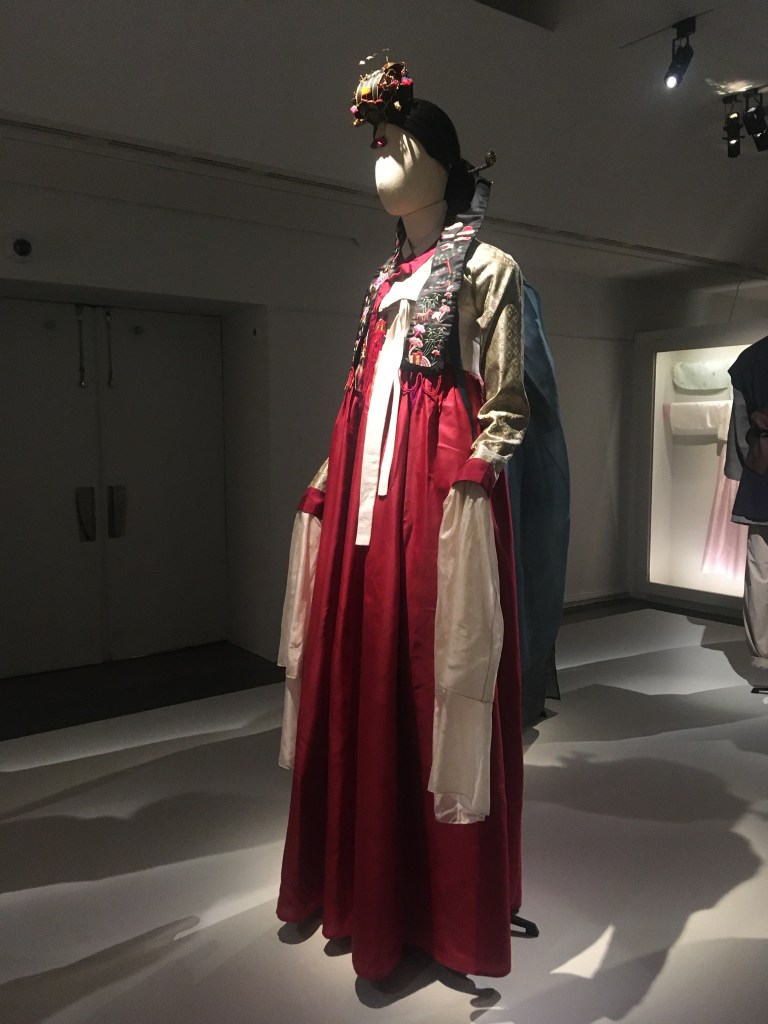

Formal attire for a court lady. Wonsam – 원삼 in Hangra-shaped silk gauze, embossed with gold and embroidered, spun with gold. Silk satin belt embossed with gold. Ornament in silk trimmings. Jeogori – 저고리 in shaped silk gauze. Silk gauze skirt embossed with gold. Wooden headdress and fake hair. Hairdressing ornaments in jade and precious stones.

The formal wear for women included a top dress called Wonsam – 원삼, the back of which was longer than the front and was worn over an apron formal skirt. The color of this garment, as well as its decoration, depended on the status of the wearer: Yellow for an empress, red for a queen, or green for a princess. This outfit was generally associated with the Keunmeoli hairstyle – 큰머리 seen previously.

Ceremonial outfit for court lady. Embroidered formal dress Hwarot – 활옷 in embroidered silk satin, belt Daedae – 대대 in gold stamped silk satin, undershirt Jeogori – 저고리 in quilted silk damask and skirt Chima – 치마 in shaped silk gauze stamped with gold. Headdress Hwagwan – 화관 in embroidered silk on cardboard frame, enameled metal ornaments and fake pearls, bun pin Binyeo – 비녀 and metal hair pendants Daenggi – 댕기, embroidered silk and applications.

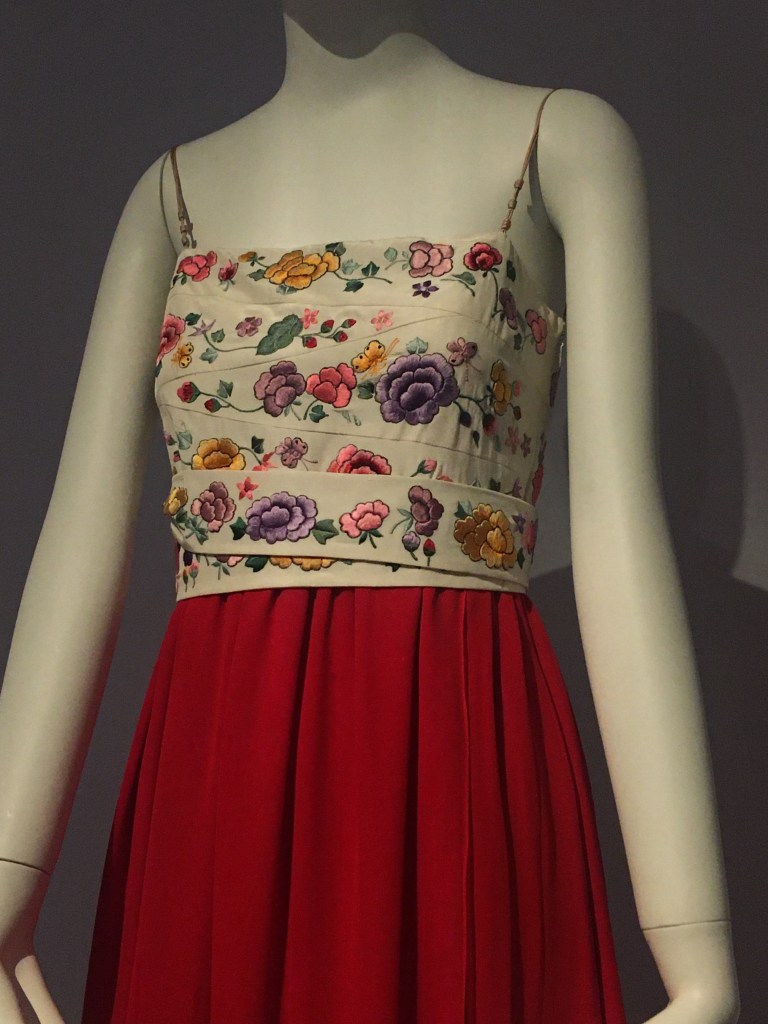

For some ceremonial occasions like weddings, women of the aristocracy wore an embroidered ceremonial dress called Hwarot – 활옷. Usually red, it was almost entirely covered with finely embroidered patterns: waves and rocks, phoenix, lotus, peonies, peaches, longevity mushrooms and pomegranates; so many auspicious symbols supposed to guarantee its carrier happiness, longevity and prosperous descendants.

Ceremonial outfit for the queen. Coat Jeogui – 적의 in silk satin, embroidery and gold thread. Belt and shoulder pendants. Apron overskirt Sang – 상, skirt Chima – 치마 and undershirt Jeogori – 저고리, organza and silk gauze, embossed with gold. Ceremonial headdress Deasu – 대수 in faux hair on metal frame, silk headbands, jade ornaments, precious stones, faux pearls, gold and enameled metal.

For the queen’s formal attire, the apron overskirt Sang – 상 and the coat Jeogui – 적의 were red embroidered with four medallions of dragons made of gold plating. Worn with the headdress Deasu – 대수, made of hair stretched over a frame and enhanced with pins Binyeo – 비녀 in the shape of a phoenix and other jade ornaments.

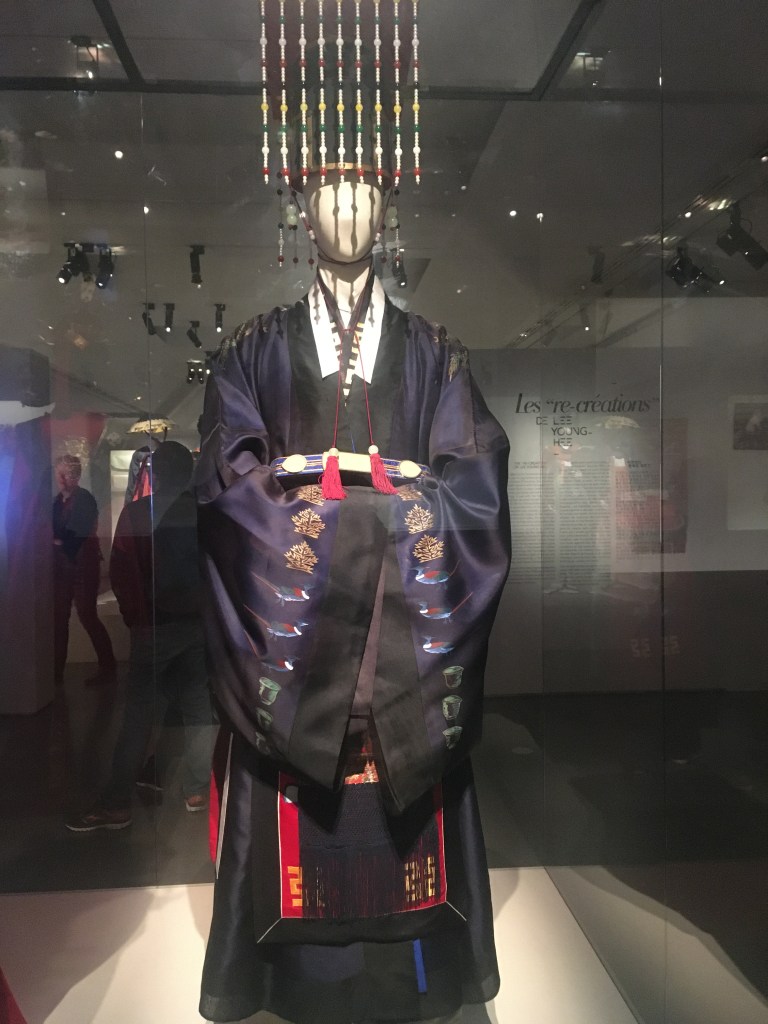

Ceremonial dress for King Myeonbok – 면복. Ceremonial coat Eui – 의 in painted silk organza, taffeta and shaped gauze. Overskirt with aprons in taffeta, gauze and velvet embroidered silk. Inner coat Jungdan – 중단, shaped gauze and embroidered silk organza, gold thread. Underwear jacket Jeogori – 저고리 and pants Baji – 바지 in silk damask. Crown Myeollyugwan – 면류관 in cardboard covered with silk, metal, trimmings, jade pearls, precious stones and false pearls. Rigid belt in glass and metal plate, pendants and jade tablet. Leather and silk shoes.

The Myeonbok – 면복 is the outfit worn by the king for the most important ceremonial occasions (sacrifices, his own marriage, reception of the Chinese emperor emissaries, …). It consists of the “garment with nine symbols” Gujangbok – 구장복 and a crown called Myeollyugwan – 면류관 adorned in front and behind with nine rows of pearls. The “nine symbols” evoke the qualities of the king. Borrowed from Ming China (1368-1644), they represent dragons, mountain, fire, pheasant, pair of sacrificial vases, algae, grains, ax and character of the two back-to-back arcs.

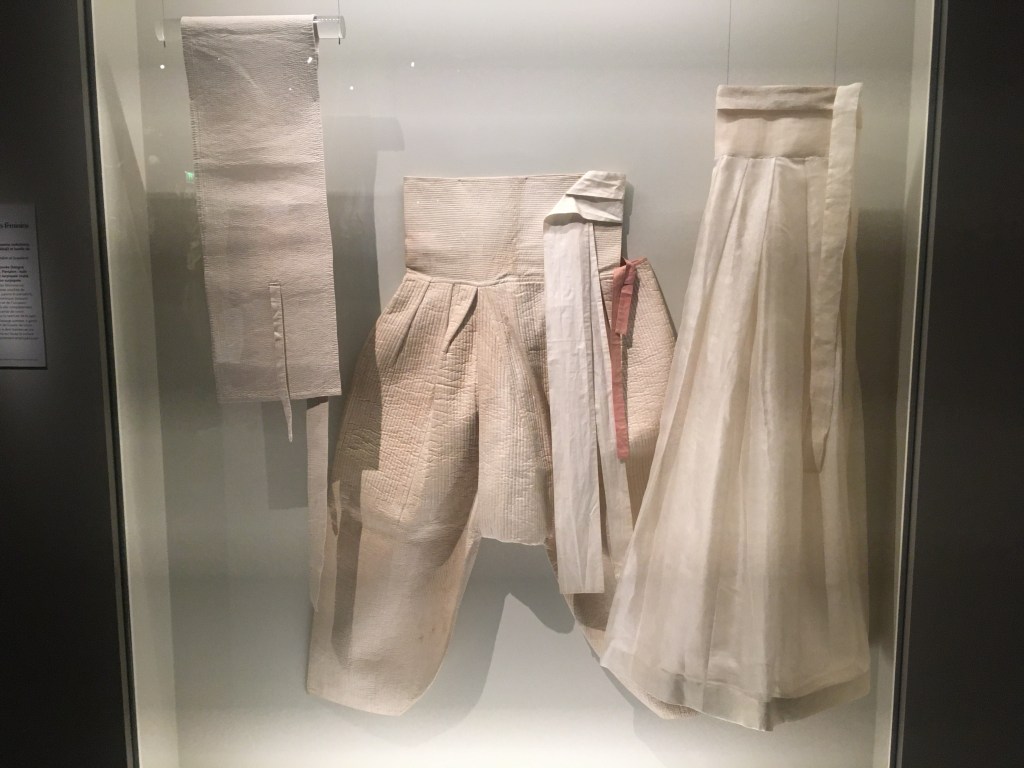

Women’s underwear. Underskirt Sokchima – 속치마 in shaped Hangra silk gauze and ramie canvas Mosi – 모시. Sokbaji – 속바지 pants in Nubi – 누비quilted cotton canvas. Topstitched cotton canvas chest band.

The volume of the female figure is obtained by the many layers of underwear: petticoats and pants, the number and materials of which varied according to the season and the occasion. The chest was completely erased using a cotton band tightly tied under the waist of the skirt.

The quilting technique consists of lining the inside of the garment with cotton quilting. This technique is called Nubi – 누비. It is frequently used for winter clothes.

Underwired cardigan and cuffs in braided bamboo mesh.

To withstand the heat of summer (hot and humid), Koreans wore a waistcoat and cuffs of braided bamboo under their clothes to prevent it from sticking to the skin.

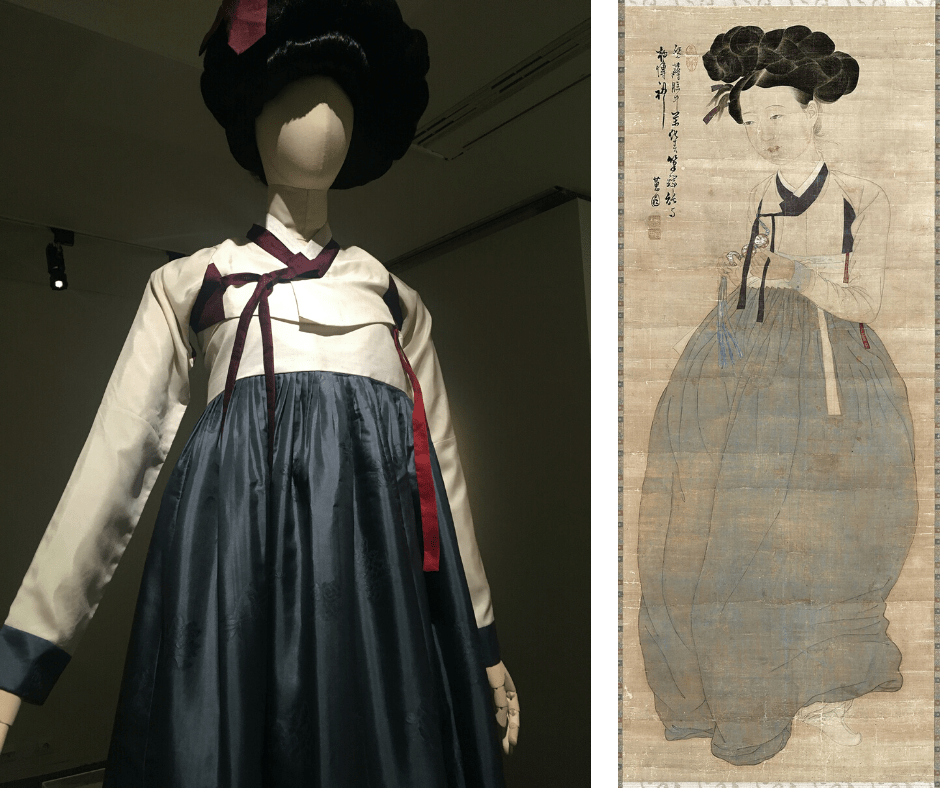

Gisaeng – 기생 courtesans’ outfits. Short jacket Jeogori – 저고리 and skirts Chima – 치마 in plain and shaped silk gauze, taffeta and damask. Pants Sokbaji – 속바지 in hand-woven and embroidered cotton canvas. Norigae – 노리개 in silk trimmings. Leather and silk damask shoes. Rattan hat and oiled paper. False hair. Metal and embroidered silk, wood and paper fans.

Courtesans were prominent in Joseon-era society. They were considered models of beauty and elegance. Often represented in painting, they played the role of fashion influencer. Their outfit plays on Korean codes of seduction, with a particularly short fitted jacket, which no longer completely hides the belt of an overly voluminous skirt, raised with ribbons to reveal pants and embroidered shoes.

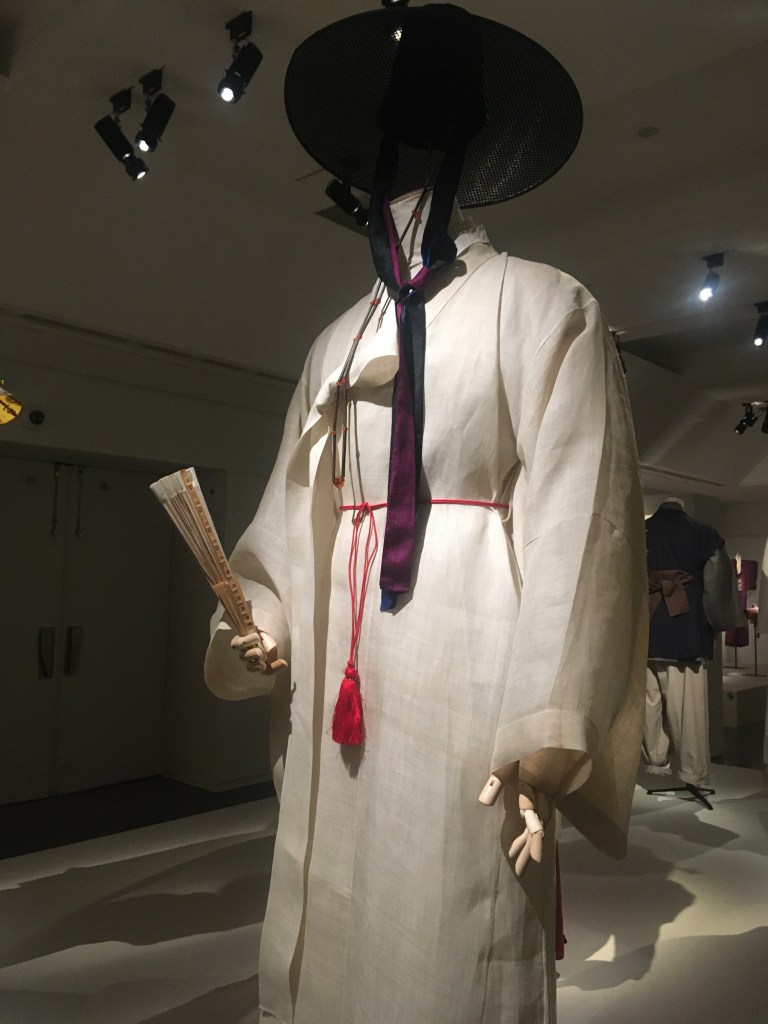

Aristocrat outfit Yangban – 양반. Coat Dopo – 도포, under jacket Jeogori – 저고리 and pants Baji – 바지 in ramie fabric Mosi – 모시. Belt Sejodae – 세조 대 in silk passementerie. Hat Gat – 갓 in lacquered horsehair mesh on bamboo frame. Fan.

The Dopo – 도포 is the coat worn by scholars and civil servants in their everyday life, adorned with a thin belt of passementerie Sejodae – 세조 대 and the male hat Gat – 갓 in black lacquered horsehair or in bamboo. Worn by the common people, the white color refers to the Korean interest for Confucian values. Bright colors were only allowed on certain occasions.

Court dancer’s outfit. Skirt Chima – 치마 in taffeta and shaped silk gauze, hand-woven cotton canvas (for the belt). Short jacket Jeogori – 저고리 in damask and silk taffeta. Hansam – 한삼 sleeve extensions in shaped silk gauze. Ornaments Norigae – 노리개 in silk and metal passementerie. Headdress Hwagwan – 화관 in embroidered silk on cardboard frame, enameled metal ornaments, faux pearls and precious stones. Bun pins Binyeo – 비 and headdress pendants Daenggi – 댕기 made of metal, embroidered silk and faux coral beads.

Soldier outfit. Military coat Chullik – 철릭 in silk taffeta and shaped gauze. Belt Sejodae – 세조 대 in silk passementerie. Underwear jacket Jeogori – 저고리 and pants Baji – 바지. Hat Jeonlib – 전립 in cardboard frame covered with vegetable fibers, gauze and silk trimmings, amber pearls. Leather shoes.

Uniforms worn by the men and women of the people. Hand-woven cotton canvas.

During the Joseon period, clothes of silk and ramie were reserved for the elite while men and women of the people wore cotton. The wearing of colors being codified and reserved for the clothes of the ruling class, white (as well as pale shades like gray and brown) was considered to be the color of the common people.

Buddhist monk’s coat call Dongbang. Cotton canvas, patchwork Bojagi – 보자기.

Mourning clothes for an official Sangbok – 상복. Ramie Mosi – 모시 and cotton canvas. Belt and hat in cardboard frame. Silk trimmings belt. Leather shoe.

Mortuary clothe. Ramie Mosi – 모시, silk organza and Hangra gauze, gold stamped for the jacket Dangui – 당의.

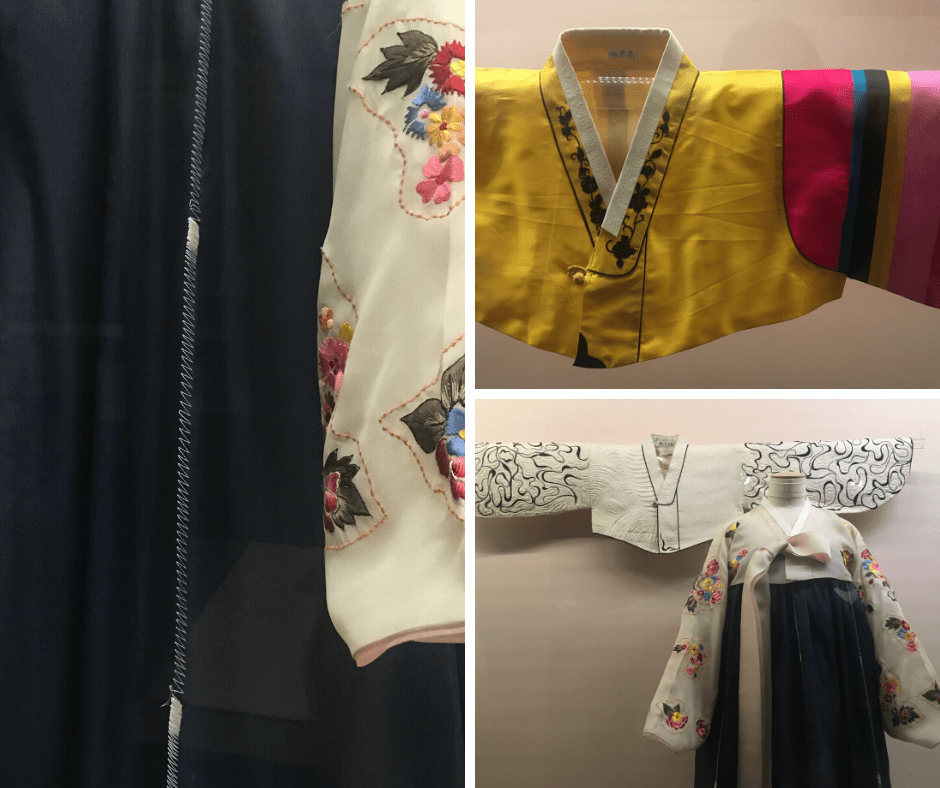

Little girl hanbok. Left: Jeogori – 저고리 in shaped silk gauze embossed with gold. Skirt Chima – 치마 in embroidered silk gauze. Right: Jeogori – 저고리 party for little girl in damask silk satin, application embroidery.

Little boy hanbok. Ramie canvas Mosi – 모시 on the left and cotton canvas on the right.

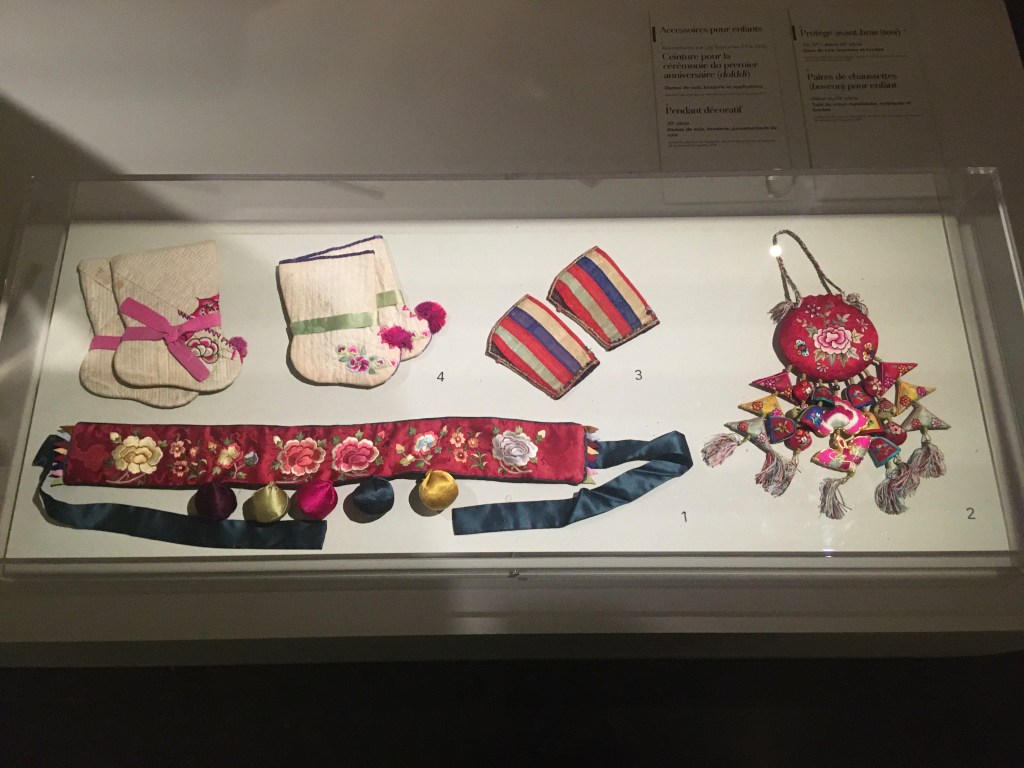

Children’s accessories. 1. Belt Dolddi – 돌띠 for the first anniversary ceremony Doljabi – 돌잡이 in silk damask, embroidery and applications. 2. Decorative pendant in silk damask, embroidery and silk passementerie. 3. Tosi – 토시 forearm protector in shaped and embroidered silk gauze. 4. Pairs of socks Beoseon – 버선 for children in quilted cotton fabric, stitched and embroidered.

Groom’s coat imitating the costume of an official. Hangra shaped taffeta, silk gauze and embroidery.

During the Joseon period, marriage was considered the utmost importante rite of passage. On this occasion, the common people, whatever their status, were authorized to wear – as an exception – court attire. The groom could wore a coat with insignia Dallyeong – 단령, a winged headdress Samo – 사모 and leather shoes, attributes of civil servants, while his wife wore a ceremonial dress Wonsam – 원삼, sometimes embroidered Hwarot – 활옷 – if her family could afford luxury clothing.

Embroidered wedding coat Hwarot – 활옷. Embroidered silk taffeta.

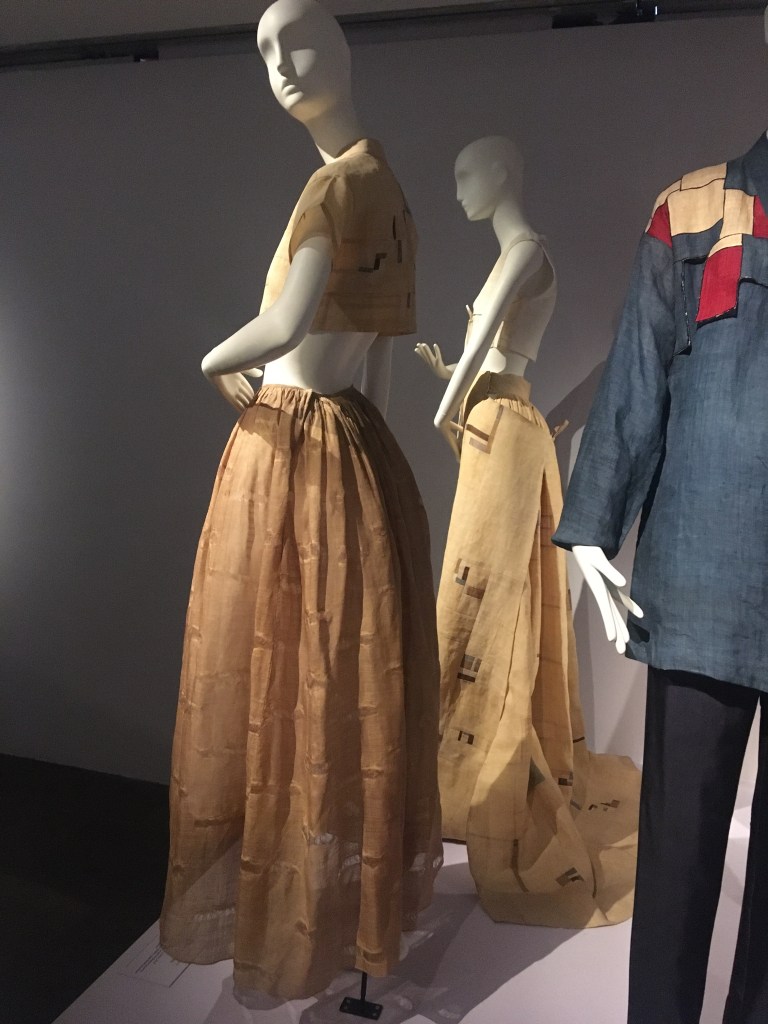

Hangra taffeta, organza and silk gauze. Hand woven cotton canvas skirt belt.

For this model, Lee Young Hee reproduce faithfully the clothes of the courtesan represented by the painter Sin Yun Bok – 신윤복 (1758-1813), in his famous Portrait of a beauty (Seoul National Museum).

” I search. Without the past, I cannot magnify the present. It’s show me the way. “

Lee Young Hee – 이영희

Favoring natural materials like ramie Mosi – 모시, gauze and silk organza, Lee Young Hee – 이영희 also tries out more unusual materials like Hanji – 한지 (Korean paper), pineapple fiber or platinum wire.

CONTEMPORARY HANBOK

Lee Young Hee was an accomplished dressmaker and a brilliant colorist. She had perfectly understood that the beauty of the Hanbok, with its characteristic silhouette, its simple and fluid lines, lies in the brilliance of the materials, the refinement of the finishes and the harmony of the colors.

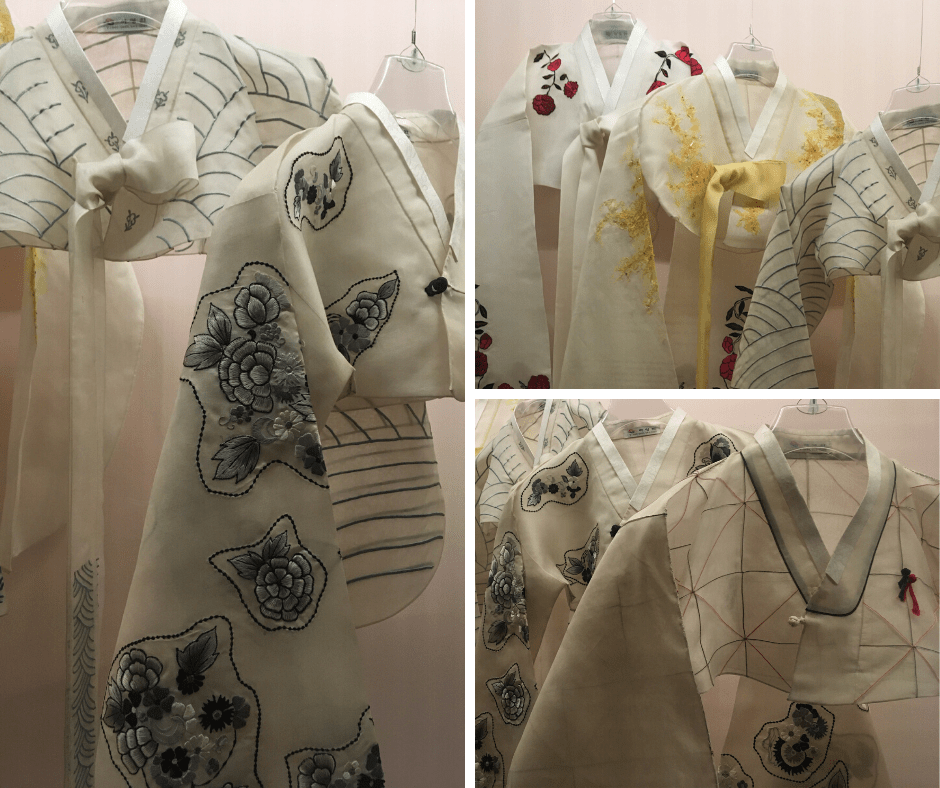

Lee Young Hee has always drawn inspiration from the sources of Korean tradition and privileged the work of natural materials, playing on the effects of textures and transparency. Whether dyed, embroidered, stitched, assembled in patchwork, painted in ink or stamped with gold, this is most often done by hand. Lee Young Hee explored natural dye to create new colorful harmonies. Often glimmering, these colors played an essential role in the success of her creations.

Jeogori – 저고리

Shaped gauze Hangra – 항라, taffeta and silk organza.

Jeogori – 저고리 worn for formal occasions are often two-tone (not counting the small white band Git – 깃 added around the neckline). They represent one or more zones of constant colors, generally a dark shade such as wine or indigo. The higher the person’s status, the greater are the number of these areas. Thus for Samhoejang – 삼회장 – formerly reserved for women of higher rank – the neck band, the ribbons, the cuffs of the sleeves, as well as the inserts at the level of the armpits Gyeotmagi – 곁마기 all use this darker shade.

Samhoejang – 삼회장. Image from SeokJuseon Memorial Museum website.

Jeogori in patchwork Jogakbo Jeogori – 조각보 저고리. Shaped gauze Hangra – 항라, organza, silk taffeta and patchwork.

Lee Young Hee applies to Jeogori – 저고리 the patchwork technique traditionally used for making Bojagi – 보자기 (wrapping fabrics). Besides the beauty of the result, we can see in this work a form of abyss since the Bojagi – 보자기 was traditionally made from the scraps of fabrics used for making clothes.

“Gray is my favorite color and the color I want to look like. It goes well with any other color. When I have trouble matching the colors of Jeogori – 저고리 and Chima – 치마, I choose gray, it instantly produces an elegant and peaceful appearance. So looking like gray, for one person, means getting along with different people. I want to be that kind of person. “

Lee Young Hee – 이영희

Striped Sleeve Jackets Saekdong Jeogori – 색동 저고리. Silk organza, gauze Hangra – 항라, taffeta, damask and embroidery.

Lee Young Hee had fun revisiting the traditional striped-sleeved jacket Saekdong Jeogori – 색동 저고리 worn by children for Chuseok – 추석, Lunar New Year Seollal – 설날 and First Birthday Doljanchi – 돌잔치. As well as by young women on their wedding day, or by shamans. The stripes of five colors refer to the five elements and five directions of the Far Eastern tradition: black (water, north), red (fire, south), green (wood, east), white (metal, west) , yellow (earth, center).

HANBOK

Wedding Hanbok. From Left to Right: Male waistcoat for silk engagement hanbok, shaped weaving brooch with golden strips. Women silk organza engagement hanbok dyed in reserve and embroidered. Wedding Hanbok in silk organza, embroidery and applications.

The traditional attire of Korean brides is composed of a red skirt (the color of young girls) and a green jacket which sometimes has striped sleeves of five colors Saekdong – 색동. This set was completed by an embroidered red Wonsam – 원삼 or coat Hwarot – 활옷.

With globalization, these traditional colors was sometimes replaced by the white of western dresses as well as by pastel shades which represent a form of compromise.

For the engagement, a ceremony which is of particular importance in Korea, the young couple will choose a pink hanbok.

Silk satin embroidered jacket

Durumagi – 두루마기 coat in quilted and silk taffeta

HAUTE COUTURE

Bringing back into Korean wardrobes the hanbok, modernized it or working for its promotion around the world was not enough for Lee Young Hee. She also wanted to enter it in the history of fashion so that it could no longer be reduced to a simple element of folklore. This is how Paris, the international fashion capital, appeared to her as an essential destination. In March 1993, she participated for the first time at Paris Fashion Week by presenting a collection at the Gabriel Pavilion. The catwalk was closed by models in traditional hanbok. From that date until spring 2004, Lee Young Hee presented two collections each year.

“Undressing clothes, I am nature. Wearing clothes, I am culture. Dream of having both nature and culture. Yes. I am wearing the Wind Costume.”

Lee Young Hee – 이영희

My Impressions

It was for me the first time, whether in France or in Korea, that I observed and contemplated so much Hanbok in the same place. The explanations were clear and concise, with just a little regret for the absence of the original words in Hangul (Korean Alphabet). It would have made my research easier.

I enjoyed the first part on accessories, Lee Young Hee’s personal collection with many vintage articles. The bun pins Binyeo – 비녀 and the embroidered fans particularly caught my attention.

I made unexpected clothing discoveries, like the undershirt and cuffs in braided bamboo to protect yourself in summer. These accessories and textile techniques confirmed me the prowess and the knowledge of the Korean textile art and increased my motivation of research around the subject. It’s unbelievable for me to think that the art of costume has hardly changed in 600 years during the Joseon era – 초선 (1392-1910), compared to our European fashion. We could (I could) conclude that there is a certain perfection and balance in the art of Korean clothing where the search for the ideal silhouette has been achieved.

The work done on the modernization of the female hanbok also inspired me concerning the choice of colors and materials declined on each garment.

After finishing the exhibition I look at Guimet Museum souvenirs shop. I bought for myself a technical introductory book about Bojagi – 보자기 by Yang Sook Choi and a traditional storybook entitled “Tiger and persimmon and other tales of Korea “, texts collected and translated from Korean to French by Maurice Coyaud and Jin Mieung Li. In these times of quarantine, I enjoy those little gifts a lot !

I HOPE YOU LIKED THIS ARTICLE!

SUBSCRIBE AND STAY ON THE WATCH!

I WISH YOU A WONDERFUL APRIL MONTH!

One thought on “THE STUFF OF DREAMS AT GUIMET MUSEUM”